The Neuroscience of Loneliness

- Lauren Lee

- Jan 29, 2025

- 5 min read

Updated: Jan 29, 2025

Welcome to the very first blog post of Brain Behind Behavior where we aim to tackle mental health challenges by exploring the connection between science and the human experience! Today we'll be examining how loneliness affects not only our emotional health but also our brain health and how we can learn to combat loneliness through intrinsic social connections in our daily lives.

In the contemporary world today, however cultured and progressive, loneliness continues to persist a perpetually unshakeable hold on a vast majority of individuals. The statistics speak for themselves: we are currently in the midst of a growing epidemic of loneliness, as observed in “a study from Cigna...showing that 46 percent of Americans felt sometimes or always alone. In 2019...the number of lonely respondents had grown to 52 percent” (Shaer). Research reveals that younger generations of Americans appear to be predominantly impacted, as “The struggle was particularly conspicuous in young respondents, ages 18 to 25, a sizable majority of whom reported acute feelings of loneliness...they had effectively withdrawn from a world that no longer had much meaning to them” (Shaer). This universal epidemic of isolation and loneliness has led the World Health Organization to proclaim it a global health concern. The real question is, how has loneliness come to afflict such widespread detriment on the modern world today?

The loneliness epidemic can be largely attributed to the alarming reduction of consistent in person contact-a previous normalcy-turned-rarity due to our heavily media-dependent culture. “Across age groups, people are spending less time with each other in person than two decades ago...this was most pronounced in young people aged 15-24 who had 70% less social interaction with their friends...Murthy said that many young people now use social media as a replacement for in-person relationships, and this often meant lower-quality connections” (Summers). The era we are all living in today-the digital age dominated by technology-is proving to be consequential in reshaping how humans communicate and interact with one another.

However, the cascade of effects doesn't just end at the social level; feeling alone is proven to have severe ramifications on our mental, physical, and neurological health. “Loneliness is a compound or multidimensional emotion: It contains elements of sadness and anxiety, fear and heartache. The experience of it is inherently, intensely subjective" (Shaer). Loneliness is strongly correlated to mental health, as communicated in a report stating that "81% of adults who were lonely also said they suffered with anxiety or depression" (Ross). Studies also show that loneliness, anxiety, and depression are interconnected through complex interactions, causing these feelings to feed into each other. This can explain why aforementioned emotions often fluctuate in tandem with one another.

Additionally, social neuroscientist Elisa Baek at USC studies the basis of social interaction. Through neuroimaging evidence, Baek found that chronically lonely people exhibit larger regions of their default mode network, a group of areas of the brain involved in high-order cognition and the integration of external world experiences into internal information. Psychologically, “The problem with loneliness seems to be that it biases our thinking. In behavioral studies, lonely people picked up on negative social signals, such as images of rejection, within 120 milliseconds—twice as quickly as people with satisfying relationships and in less than half the time it takes to blink" (Zaraska). Ultimately, "'Social connections matter for our cognitive health'" (Summers).

Furthermore, human connection is paramount to our physiological brain health. Physically, "loneliness raises our blood pressure, negatively alters our cognitive functions, is associated with Type 2 diabetes and shortens our life spans. (Subsequent studies have linked the emotion to suicidality, Alzheimer’s and leukemia)" (Shaer). Moreover, “the physical consequences of poor connection can be devastating, including a 29% increased risk of heart disease; a 32% increased risk of stroke; and a 50% increased risk of developing dementia for older adults", a startling statistic that sharpens our perception of lonelin ess and clarifies the damaging and endangering health effects of feeling alone, especially for the older population who are more susceptible to such outcomes.

The neurology and psychology behind loneliness is explicative of the internal experience every single human being undergoes at some moment in their life. According to Hawkley and Cacioppo's biological approach, our brains have gradually evolved to prioritize an innate sense of togetherness. When we fail to find it, we automatically generate an anxiety response. In a cited study, "brain

scans of the excluded participants demonstrated ‘neural activation localized in a dorsal portion of the anterior cingulate cortex that is implicated in the affective component of the pain response.’ This means that the pain the subjects were feeling was indicative of the fact that loneliness is a biological signal. Hawkley explained, "It’s supposed to motivate us and tell us we need more people around us or that we need support. It tells us that something is wrong” (Shaer). To put it simply, loneliness is controlled by our brain. If it's not mitigated, the brain can trigger feelings of anxiety, stress, and depression.

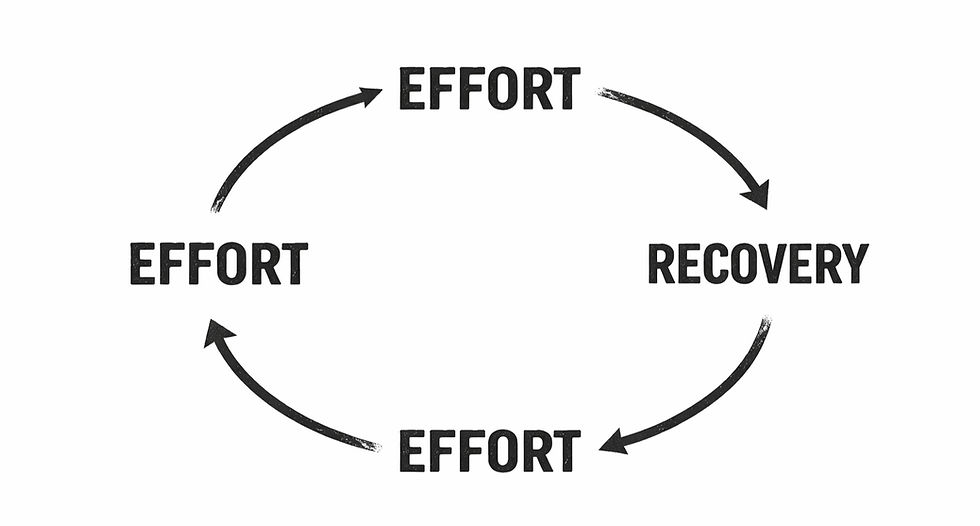

We also find ourselves stuck in seemingly inescapable negative loops called feedback loops. "'A person desperately wants not to be lonely, but fear and anxiety have convinced them their loneliness reflects a fundamental undesirability. ‘They are absolutely certain that they’re not worth talking to, that no one likes them, that they’re not a good person and that it’s all their fault...The brain is being hijacked’” (Shaer). Such a feeling reprograms the mind to develop an unhealthy perception of self, a mental shift akin to anxiety.

Now that we know how gravely debilitating loneliness can be on our physiological and psychological health, how can we address this issue that seems to be such an innate part of the human experience? The answer to this question lies in, not just the world around us, but our internal state that profoundly governs our interpretations of external stimuli.

Cognitive science research encourages synchrony as a key to understanding how behaviors and reactions match from movement to movement between people who like and trust one another. "This synchrony between individuals can be as simple as reciprocating a smile or mirroring body language during conversation, or as elaborate as singing in a choir or being part of a rowing team" (Zaraska). Lonely people struggle to synchronize with others, so learning how to join the action of others can foster valuable human connection.

Remedies we can integrate into our daily life to help us tackle loneliness:

1) Reach out to family or friends. The positive emotional experience we feel when we are surrounded by people that make us feel safe and accepted strongly mitigates the link between our negative interpretations of negative stimuli and loneliness. Strengthening your existing relationships and reaching out for support can significantly help us overcome loneliness.

2) Learn to love yourself. Building self-love and confidence can enable us to be comfortable in our own company. Loving yourself through feelings of loneliness reinforce the embracement of the indelible truth that we are good enough. Feeling lonely does not make this untrue.

3) Learn to be forgiving of others. Forgiveness can reduce negative emotions of depression, resentment, and hurt. It frees us from our past grievances and the isolating barriers we often tend to create around ourselves as a result of feeling lonely.

4) Find ways to help others. Studies show that activities such as volunteering is proven to boost a positive mood, cognitive function, and wellbeing. Finding a sense of purpose in life helps reduce feelings of loneliness, and it also opens new opportunities for seeking friendship and connection.

Comments