The Science of Procrastination

- Lauren Lee

- Feb 12, 2025

- 6 min read

Welcome to the second blog post of Brain Behind Behavior! Today we will be investigating the neural roots of procrastination, the integral role that dopamine plays, and how to overcome it based on neuroscience.

Procrastination holds a major grip on society. The indelible truth is, we have all procrastinated at multiple point in our lives, whether it be in our academic, work, or daily lives. Personally, I struggle with procrastination quite a lot as a high school student. I often find myself delaying my homework, avoiding studying for an upcoming test, or putting aside an important class project until the deadline. It is incredibly easy to fall into the trap of procrastinating on tasks we simply need to complete.

In etymological terms, the word "procrastination" was derived from procrastinare, a Latin verb meaning-to put off until tomorrow. It can also be derived from an ancient Greek word Akrasia-to do something against our better judgement. Professor of motivational psychology at University Calgary says "it's self-harm" (Lieberman). Self-awareness is the cause of why procrastinating always makes us feel absolutely rotten because we are not only aware that we are avoiding the task in question, but that procrastinating itself is a poor choice of action. In other words, we are completely aware of the fact that we are making a bad decision.

Despite the immense ramifications on life that procrastination presents, it remains to be a universal habit. "An estimated 20% of adults (and above 50% of students) regularly procrastinate" (Ling). This voluntary and unnecessarily delaying of tasks is extremely widespread. Chronic procrastinators perform worse in their academics and earn less money and less valued jobs. One can even develop lower self esteem and a lack of self care.

Not only does procrastinating impact our work and daily life, people that chronically procrastinate experience high levels of stress and numerous health problems. Headaches, insomnia, and digestive issues are common after effects, and individuals become more susceptible to colds and the flu. To an even further extent, procrastination can contribute to hypertension and cardiovascular disease, revealing the severe risks of a largely normalized habit.

A Case Western psychological science study examined procrastinating college students' academics, stress, and health. They found that "the costs of procrastination far outweighed the temporary benefits. Procrastinators earned lower grades than other students and reported higher cumulative amounts of stress and illness. True procrastinators didn’t just finish their work later—the quality of it suffered, as did their own well-being" (Jaffe). This is something that everyone has experienced-specifically students, who are faced with a demanding workload that can often seem too overwhelming to undertake.

Procrastination is not simply the result of having poor time management skills. In reality, scientific evidence reveals that it is actually a result of poor mood management and having an overall poor emotional response to things in life. Because procrastination is essentially a way to cope with the negative emotions or moods induced by particular tasks, "procrastination is about being more focused on ‘the immediate urgency of managing negative moods’ than getting on with the task, Dr. Sirois said” (Lieberman). Whether it be a homework assignment, an upcoming exam, or something as simple as cleaning your room, emotions such as frustration, self-doubt, anxiety, and insecurity can be triggered.

This aversion of completing a task can be blamed on an inherently unpleasant aspect of the task itself. However, it might stem from deeper feelings that are related to the task. As previously mentioned, debilitating feelings like self-doubt, low self-esteem, insecurity, or anxiety may be the root of the cause. We often go through an entire thought process that leads us into a mental downward spiral. "Staring at a blank document, you might be thinking, I’m not smart enough to write this. Even if I am, what will people think of it? Writing is so hard. What if I do a bad job? All of this can lead us to think that putting the document aside and cleaning that spice drawer instead is a pretty good idea" (Liberman). Even though procrastination seems like the optimal solution at the moment, avoiding the task at hand is a temporary fix that only prolongs what inevitably needs to be accomplished. And the problem remains: those negative associations we have with the task will still be there when we come back to it, and feelings of stress will increase as well.

Now let's tackle the neurological underpinnings of procrastination. An important part of the brain that is linked to procrastination is the amygdala: a region of the brain that processes emotions and signals alerts when it senses a threat, initiating a "fight or flight" response. The amygdala perceives the task as a threat to our self-esteem or well-being. And despite knowing that putting off the task will cause ourselves to experience more stress in the future, our brains are wired to be more concerned with removing the threat. Researchers are calling it the "amygdala hack." Interestingly, those who procrastinate chronically tend to have a larger volume of gray brain matter in the amygdala, meaning they will be more sensitive to the potentially negative consequences of their actions, in turn leading to increased negativity and procrastination. Hence, so many people fall victim to the chronic, addictive cycle of procrastination.

Additionally, a small piece of tissue in the brain, called the parahippocampus, is key to the emotional aversiveness of procrastination. “This is because the parahippocampus additionally communicates with other neighboring brain regions in the limbic system. In procrastinators, this whole region works together to amplify an event’s aversiveness...Next, the temporal discounting piece in procrastination kicks in, leading procrastinators to feel less motivated to get started on an event that seems far away... procrastinators may have less neural tissue in the prefrontal area of the brain (involved in planning and impulse control), making it more difficult for them to self-regulate their use of time. Without the ability to self-regulate, you’ll find it more difficult to place yourself as you try to achieve a goal within the allotted time limits" (Whitbourne). Ultimately, chronic procrastinators are only capable of thinking of how frustrating, boring, or unfulfilling the task will be. That is, until the inevitable happens and they have no other choice than to finally tackle it.

The goal is to learn how to get things done without procrastinating. This goal, however impossible or difficult it appears to be, is achievable, and it can significantly reduce the amount of stress and anxiety you feel in your everyday life.

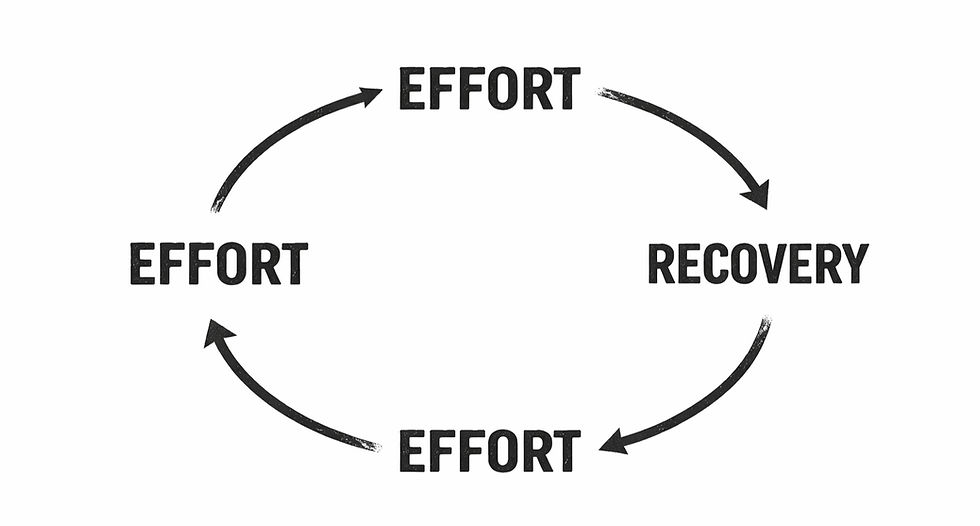

1) Focus on your mood. Do not force yourself to do a certain task. Remember, procrastination is entirely about your emotions, not your lack of productivity. Downloading a time management app or moving distractions out of reach will not help address the core problem. You must learn how to manage your emotions differently. Basically, our brains are constantly seeking relative rewards. Experiencing habit loops around procrastination will prolong our search for a better reward, causing our brains to keep on procrastinating over and over again until we finally give ourselves something better to do. Neuroscientist, psychiatrist, and Director of Brown University's Mindfulness Center Dr. Brewer states that in order to rewire any habit, we must give our brains the "Bigger Better Offer". To tackle our procrastination, we need to find a better reward other than avoidance. We need a reward that can relieve us of the challenging feelings we have at the present moment that will not cause harm to our future selves. The solution lies internally.

2) Improve your temporal thinking. Studies show that people who imagine a version of themselves two months into the future twice a week for 10 minutes are less likely to procrastinate. This practice is an effective way to increase your motivation towards your future self by reducing your procrastination in the present moment. Having a mentality that choosing to not procrastinate is a way of investing in your future, and investing in yourself.

3) Start small. For example, if you have been putting off a project, make a deal with yourself, as Instagram founder Kevin Systrom said. "'If you don’t

want to do something...make a deal with yourself to do at least five minutes of it. After five minutes, you’ll end up doing the whole thing'" (Haden). Who knew something as simple as spending five minutes on a task could get you out of your procrastination loop? Your limbic system rejects the idea of five hours, but commit to five minutes and once you get started, whatever you were afraid of beginning doesn't seem so scary after all. Your body and your mind will immediately jump into a work mode: your endorphins kick in, your mental muscles get warm, and your limbic system will embrace these new feelings. So, when you find yourself struggling to start on a task, don't overwhelm yourself and think about all the work that it will involve. Commit to five minutes, calm your limbic system, and conquer that to-do!

4) Give mindfulness a go. Practicing non-judgemental awareness and attentiveness to your body's reactions through simple mindfulness exercises like breathing or medication can create less of a tendency to procrastinate. Letting your negative emotions take over will only lead to a downward spiral, and you will ultimately resort back to procrastination. Rather, reappraise the task. Create meaning and connection to the task. Dial down on your emotions to make them more manageable. Clearing your headspace and calming your emotions is a powerful tool to combatting procrastination.

Comments